I feel sad that I am starting to think about museums and galleries the way I think about zoos. Since reading Geoffrey Robertson’s book, Who Owns History and watching shows such as Stuff the British Stole , I have a greater awareness of the practices behind the growth of the collections.[1][2] I can no longer go to zoos. It hurts me too much to see animals in captivity. I still go to museums and galleries, but I feel guilty.

Having collections (of animals or objects) helps us learn about them and appreciate them. But I also wish that they could be where they are meant to be. This issue is massive and complex, so I will not get into it further here except to say that I think it is important, when viewing collections, to understand the context and history, not just of the cultures that they came from but how they came into the collections. Unfortunately, I usually find the short descriptions in museums frustratingly inadequate for this purpose.

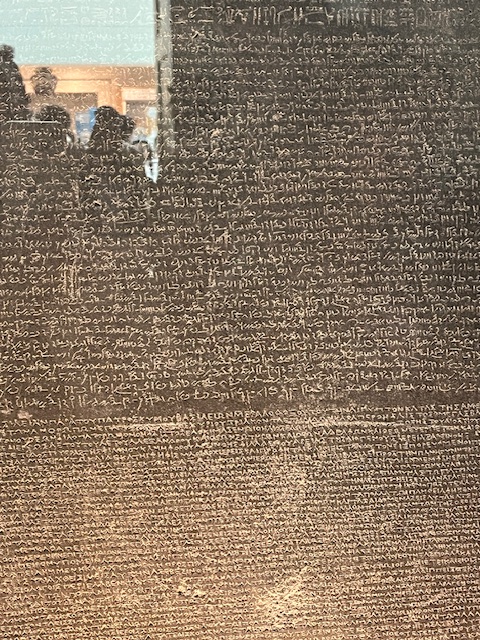

Rosetta stone (room 4). My first university degree was in prehistory and archaeology. So you can imagine how excited I got when I realised that one of the exhibits in the British Museum is the Rosetta Stone. The actual real Rosetta Stone. For those of you who are unfamiliar with it, the Rosetta Stone was the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. It contains a decree written in three different scripts in Egypt in 196 BC. One of the scripts is Ancient Greek, which was already known, so it was used to decipher the other scripts.

For me, the Rosetta Stone symbolises research and understanding, the joy of discovery and the value of good historical documentation!

Robertson says that the Rosetta Stone is one of the objects in the museum which appears to have been obtained legally and, since he is a barrister, I will take his word for it.[1] It was found by French soldiers and surrendered to England as part of the peace treaty after their defeat at Aboukir Bay. One reason that there is no pressure to return it to Egypt is that many others have since been found. There are seventeen others in the Cairo Museum. [1] pp179-180

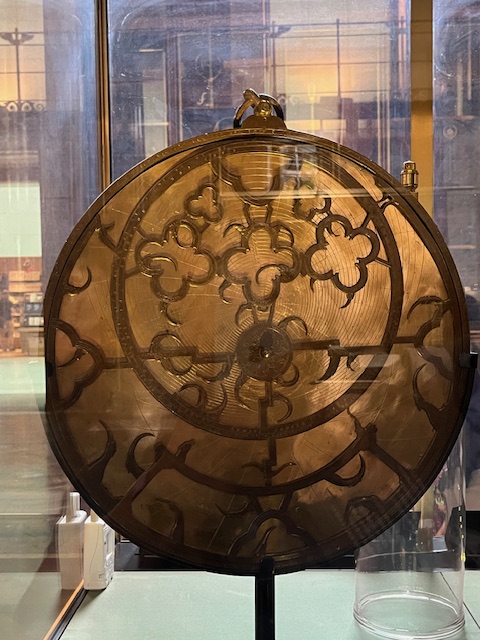

The Sloane Astrolabe (room 1) crafted around 1300, it is one of the oldest mathematical instruments in the museum. An astrolabe is an astronomical instrument, used to identify stars or planets, determine latitude and tell time. It is a precursor to the sextant.

This Astrolabe was owned by Hans Sloane and it was his collection that became the basis for both the British Museum and the British Library. While his collection was seemingly bequeathed to the King quite legally, as a collector he was not without controversy. He worked as a doctor on slave plantations in Jamaica and it is claimed that is how he financed his collection.[3] In 2020, a bust of Sloane was removed from display within the museum in what the Director of the Museum described as an acknowledgement of links to slavery and a commitment to a ‘rewrite our shared, complicated and, at times, very painful history.’ [4]

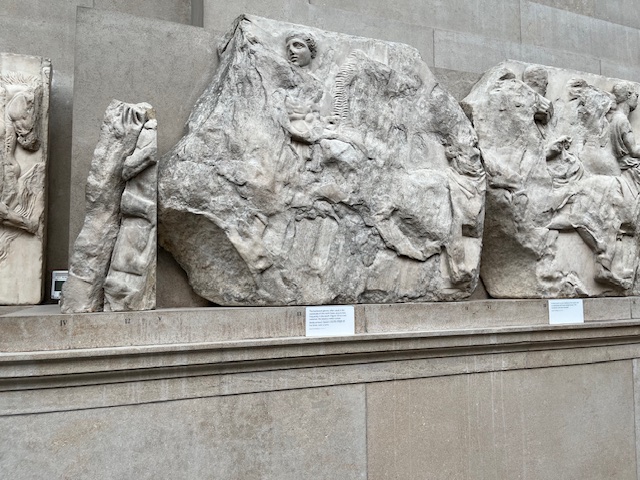

The Parthenon sculptures (room 18) are from the Parthenon temple in Athens and date to between 447BC and 432BC. Renamed by the museum from ‘the Elgin marbles’ in an obvious attempt to try to disentangle them from the person who stole them from Greece, they are perhaps the most well known of the contested items in the museum. I will not get into the debate here, but if you are interested in it, Geoffrey Robinson’s book presents the case for their return to Greece and the museum’s website presents the case for them remaining in England. The fact that they need three rooms to display them emphasises the scale of the act.

Special exhibitions

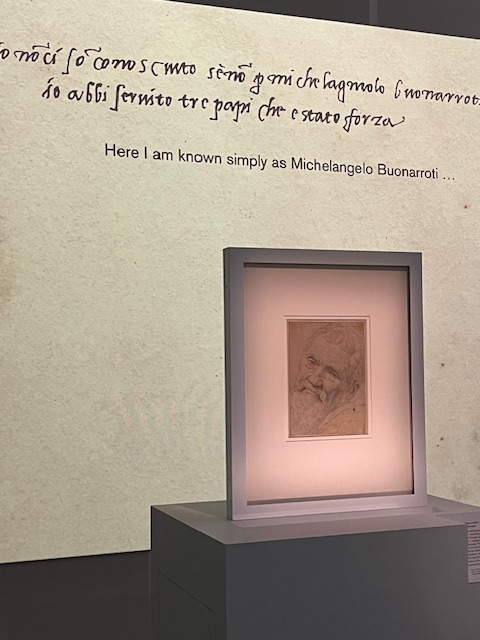

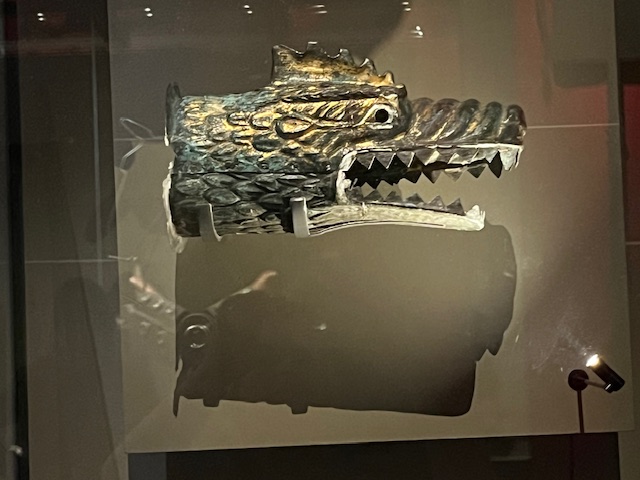

There is so much to see in the museum, I could probably have spent a week there. Instead I visited two paid exhibitions – Michelangelo and the Romans. Just a couple of photos for you here:

Sources

- Robertson, Geoffrey, Who Owns History? Elgin’s Loot and the Case For Returning Plundered Treasure, Random House Australia, 2019

- Stuff the British Stole, ABC Australia

- Anonymous, ‘Sir Hans Sloane‘, British Museum, The British Museum Story,

- White, Adam, ‘British Museum removes bust of slave-owning founder Sir Hans Sloane: ‘We have pushed him off the pedestal’, Independent, 25 August 2020,

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/parthenon-sculptures

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/parthenon-sculptures/parthenon