If you have been following my travel posts you will have noticed by now that I love museums and art galleries. So, of course, I had to visit Penlee House while in Penzance as it has both.

You may be wondering what Penlee House has to do with the Bronte family and if you read their website you would be no wiser about the connection, as they do not mention it. I read on some other websites that the mother and aunt of the Bronte sisters, Maria and Elizabeth Branwell, lived on Chapel Street and one mentioned that they came from a successful Penzance family of merchants. [1] Penlee House was built in 1864 for ‘the wealthy Penzance miller and merchant, John Richards Branwell’. So of course, the genealogist in me immediately asked, can I find a connection between these families?

But first, a bit about Penlee House and its collections.

Penlee House is located in Penlee Park, a short walk from my accommodation. It was bought for the town in 1946 as a War Memorial, and to house historic and art collections. The original museum dates back to 1839 and its focus was, like many of that time, natural history and ‘antiquities’. It still houses exhibitions about Cornwall’s past, including archaeological discoveries and the history of mining. It also hosts art exhibitions featuring local artists and artists from the Newlyn School of art. Newlyn is the next town along from Penzance and the Newlyn School was a colony of artists that were resident there in the late 1880s.

The Bronte connection

So, back to the Bronte sisters and the Branwell families.

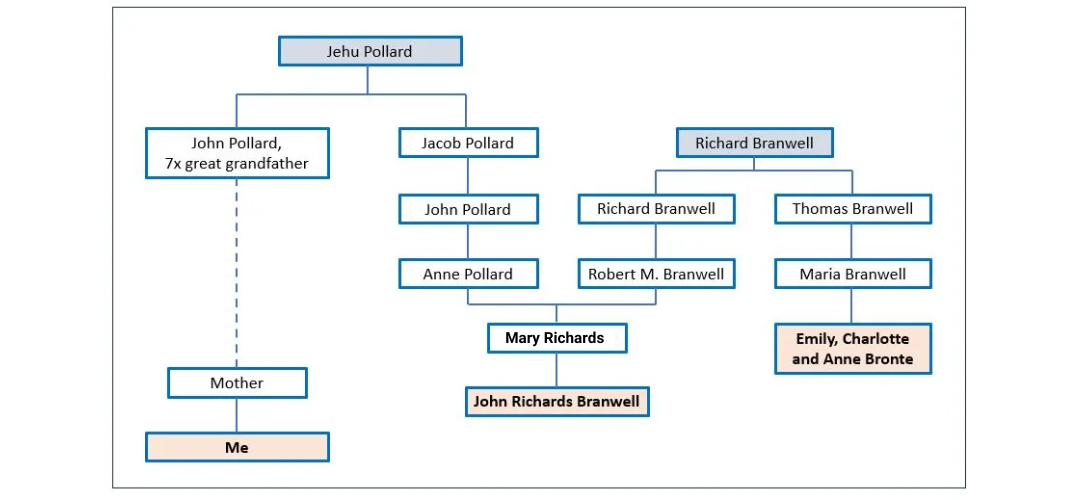

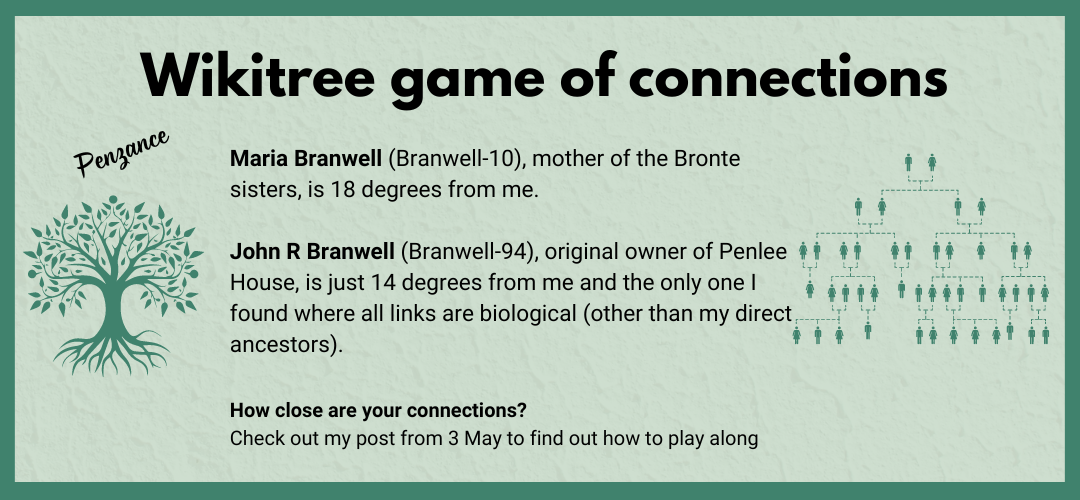

I researched John Richards Branwell, the original owner of Penlee House. I added him to Wikitree, then extended his family back in time. I got a wonderful surprise then, as Wikitree informed me that he was related to me! Fourth cousin five times removed, but that kind of distance does not bother us genealogists! It turns out that his grandmother was Anne Pollard and the mother of my Cornwall convict (Lydia Matthews) was also a Pollard.

Maria Branwell was born in Penzance in 1783, to Thomas Branwell and Anne Carne. [2] It was a little tricky finding the connection as the Branwells were not terribly imaginative with their sons’ names, so there were a lot of Richards, Roberts and Johns, and I had to correctly allocate each to the right family. Eventually, though, I made the connection. John Richards Branwell, owner of Penlee House, was the second cousin once removed of the Bronte sisters.

Sources

- Holland, Nick, ‘The Brontes and the Cornwall Connection‘, Anne Bronte, 2 July 2017

- Anon, ‘Maria Branwell‘, Wikipedia; ‘Maria Bronte formerly Branwell‘, Wikitree